Falling Groundwater & Upcoming Water Crisis in Bihar

Groundwater is water that has infiltrated the ground to fill the spaces between sediments and cracks in the rock. Groundwater is fed by precipitation and can resurface to replenish streams, rivers, and lakes.

Water that has traveled down from the soil surface and collected in the spaces between sediments and the cracks within the rock is called groundwater. Groundwater fills in all the empty spaces underground, in what is called the saturated zone, until it reaches an impenetrable layer of rock. Groundwater is contained and flows through bodies of rock and sediment called aquifers. The amount of time that groundwater remains in aquifers is called its residence time, which can vary widely, from a few days or weeks to 10 thousand years or more.

The top of the saturated zone is called the water table, and sitting above the water table is the unsaturated zone, where the spaces in between rocks and sediments are filled with both water and air. Water found in this zone is called soil moisture and is distinct from groundwater.

Existing groundwater can be discharged through springs, lakes, rivers, streams, or manmade wells. It is recharged by precipitation, snowmelt, or water seepage from other sources, including irrigation and leaks from water supply systems.

To artificially discharge groundwater, a well must be drilled into an aquifer, and a well typically requires a pump to move water upward out of the aquifer. Artesian wells are drilled into aquifers that are bounded by an impenetrable rock layer from both above and below and water pressure from a recharging source located above the well outlet point will cause groundwater to be pushed upward through the artesian well, making the use of a pump unnecessary.

One important reason why groundwater is extracted through wells is to provide drinking water.

HOW MUCH DO WE DEPEND ON GROUNDWATER?

The National Commission on Integrated Water Resources Development (NCIWRD) report, the utilizable water is 1,123 billion cubic meters a year, comprising 690 billion cubic meters of surface water and 433 billion cubic meters of replenishable groundwater.

More than 90 percent of groundwater in India is used for irrigated agriculture. The remainder — 24 billion cubic meters — supplies 85 percent of the country's drinking water. Roughly 80 percent of India's 1.35 billion residents depend on groundwater for both drinking and irrigation.

Despite this, we have an extremely poor understanding of groundwater, which impacts both policy and practice.

Groundwater contamination-

Groundwater contamination is the presence of certain pollutants in groundwater that are in excess of the limits prescribed for drinking water. The commonly observed contaminants include arsenic, fluoride, nitrate, and iron, which are geogenic in nature. Other contaminants include bacteria, phosphates, and heavy metals which are a result of human activities including domestic sewage, agricultural practices, and industrial effluents. The sources of contamination include pollution by landfills, septic tanks, leaky underground gas tanks, and overuse of fertilizers and pesticides. It has been pointed out that nearly 60% of all districts in the country have issues related to either availability of groundwater, or quality of groundwater, or both.

The Committee on Estimates 2014-15 that reviewed the occurrence of high arsenic content in groundwater observed that 68 districts in 10 states are affected by high arsenic contamination in groundwater. These states are Haryana, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, West Bengal, Assam, Manipur, and Karnataka.

Groundwater extraction and use-

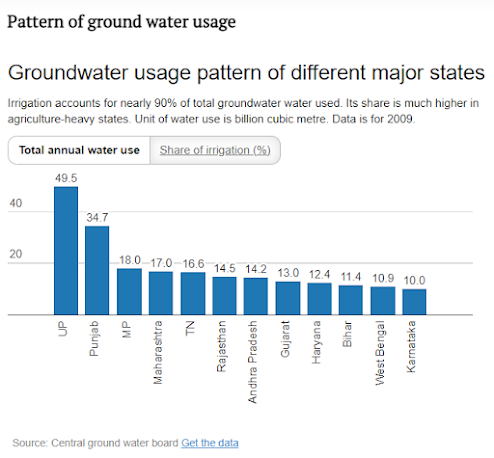

Experts believe that India is fast moving towards a crisis of groundwater overuse and contamination. Groundwater overuse or overexploitation is defined as a situation in which, over a period of time, The average extraction rate from aquifers is greater than the average recharge rate. In India, the availability of surface water is greater than groundwater. However, owing to the decentralized availability of groundwater, it is easily accessible and forms the largest share of India’s agriculture and drinking water supply. 89% of groundwater extracted is used in the irrigation sector, making it the highest category user in the country. This is followed by groundwater for domestic use which is 9% of the extracted groundwater. Industrial use of groundwater is 2%. 50% of urban water requirements and 85% of rural domestic water requirements are also fulfilled by groundwater.

Irrigation through groundwater-

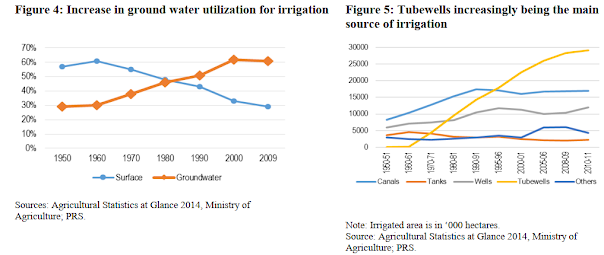

The largest component of groundwater use is the water extracted for irrigation. The main means of irrigation in the country are canals, tanks, and wells, including tube wells. Of all these sources, groundwater constitutes the largest share. Wells, including dug wells, shallow tube wells, and deep tube wells provide about 61.6% of water for irrigation, followed by canals with 24.5%. Over the years, there has been a decrease in surface water use and a continuous increase in groundwater utilization for irrigation. Figure 5 illustrates the pattern of use of the main sources of irrigation.

As can be seen, the share of tube wells has increased exponentially, indicating the increased usage of groundwater for irrigation by farmers. The dependence of irrigation on groundwater increased with the onset of the Green Revolution, which depended on the intensive use of inputs such as water and fertilizers to boost farm production. Incentives such as credit for irrigation equipment and subsidies for electricity supply have further worsened the situation. Low power tariffs have led to excessive water usage, leading to a sharp fall in water tables.

A sharp dip in water table across Bihar-

EXPLAINED

Why water table is dipping in Bihar-

Why is it that we neither understand nor prioritize groundwater in our policies?

This is large because of two reasons: Groundwater is invisible—it is literally not visible to the eye because it is well below the ground. What is out of sight, is usually out of mind! Groundwater is also a highly complex subject that is governed by many ‘conditionalities’. It is this ignorance, by both users and people in governance, that has contributed to the situation we find ourselves in today.

Moreover, groundwater education still focuses largely on ‘exploring’ new sources of groundwater that will lead to the ‘development of groundwater resources. The subject of groundwater in aquifers is often considered quite complex as compared to providing groundwater supplies from wells, even if these wells continue to become deeper and deeper as groundwater levels decline. In the gap between supply on one side and demand on the other, we are losing out on components of groundwater management from many systems of education delivery.

We need a demystified but correct understanding of aquifers (underground rocks that are sources of groundwater), their properties, and how they are used so that we can make the critical mass of users and decision-makers understand them and act on them appropriately.

There are basically three issues. The first is depletion. Our wells and springs are drying up, and as a consequence of this depletion, our groundwater quality is also deteriorating.

When there is less water in an aquifer, the concentration of ions increases. When aquifers get recharged sufficiently, contaminants are diluted. Whether it is groundwater use in agriculture or in domestic supply, serious issues of contamination like fluoride and arsenic, which are no longer isolated cases and are found across large regions of the country, must be addressed. This contamination is the second problem, and it is very often related to the first problem of depletion.

The third, which is not readily perceived as a problem, is that of the increasing disconnect between groundwater and ecosystems, particularly due to the environmental impact of depletion and contamination. As a consequence of large-scale groundwater usage for human needs, the value of the service that aquifers provided to the environment—say to river flows—has significantly reduced.

What is it that India needs to do?

If we are to address our water problems, there are a few things that the country needs:

Aggregate micro-level solutions to construct a larger picture that can inform policy, Groundwater in India is rather disaggregated in terms of its occurrence, usage, and problems. Hence, we need disaggregated approaches leading to customized solutions that are appropriate to locations and situations of groundwater problems. Further, it is important to pull together these smaller solution pieces to construct a larger picture. This is the reason why we need practitioners who have worked on the ground and attempted to solve the problems, to be actively involved in policy framing; else, things will not change and the divide between policies, and practices on groundwater management will only continue to widen further.

Stronger public institutions are dedicated to groundwater management, Additionally, we have an institutional vacuum when it comes to dealing with groundwater. Let us consider an example from Maharashtra. More than 80 percent of Maharashtra’s rural drinking water supply comes from groundwater wells. Protecting and sustaining this source is a function of how groundwater is used in agriculture so that the drinking water supply in the villages of the state remains secure.

The Ground Water Survey and Development Agency (GSDA) falls under the ambit of the Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation. It has little to do with water used for agriculture—which accounts for less than 5 percent of water used in rural Maharashtra—and hence cannot influence policy or usage with respect to that. Organizations like GSDA must be strengthened and encouraged to engage in partnership models of working with grassroots organizations that are working on community-level water management.

This is just one example of how a lack of institutional thinking impacts solutions. Many states don’t even have a GSDA equivalent. Strengthening agencies dealing with groundwater becomes quite important in this regard.

To demystify the science and involve people in solution-making. Some important questions we need to consider include: How does one get people to participate and cooperate in efforts dealing with groundwater management? How do communities convert competition and conflict to participation and cooperation? Our experience at ACWADAM is that when you undertake an effort in demystifying science and involve communities and committed people in the development of that science, you can achieve improved decision-making at any level. And once you achieve this, your outcomes automatically change even though they are often not ideal. However, even such imperfect outcomes significantly enhance water security in regions that depend on groundwater.

With more attention and investment in promoting partnerships and collaborations, there is a grave need for infusing interdisciplinary science into the processes of groundwater management and governance. Only if and when such science is made to bear upon achieving decentralized water governance, will we be able to solve many problems on groundwater. It is important, therefore, to realize that no single agency holds the key to problem identification and resolution in the sector of groundwater. Hence, catalyzing collaborations that integrate the many disciplines required to develop sustainable groundwater management solutions, is needed; such partnerships must form the backbone of public efforts to protect, restore, and manage groundwater resources.

Legislative and Policy Framework-

Currently, the Easement Act, 1882 provides every landowner with the right to collect and dispose of, within his own limits, all water under the land and on the surface. This makes it difficult to regulate the extraction of groundwater as it is owned by the person to whom the land belongs. This gives landowners significant power over groundwater. Further, the law excludes landless groundwater users from its purview. Waterfalls under the State List of the Constitution. This implies that state legislative assemblies can make laws on the subject. In order to provide broad guidelines to state governments to frame their own laws relating to sustainable water usage, the central government has published certain framework laws or model Bills. In 2011, the government published a Model Bill for Ground Water Management based on which states could choose to enact their laws. In addition, it outlined a National Water Policy in 2012 articulating key principles relating to demand management, usage efficiencies, infrastructure, and pricing aspects of water. As recommended in this policy, the government published a National Water Framework Bill in 2013.

The Model Bills and National Water Policy address the governance of groundwater under the public trust doctrine. The concept of the public trust doctrine ensures that resources meant for public use cannot be converted into private ownership. The government is the trustee has the responsibility to protect and preserve this natural resource for and on behalf of the beneficiaries, that is, the people. Additionally, they allow every person the fundamental right to be provided water of acceptable quality. It may be noted that the fundamental right to water has been evolved by the Supreme Court and various High Courts of the country as part of the ‘Right to Life’ under Article 21 of the Constitution. Courts have delivered verdicts on concerns such as access to drinking water and on the right to safe drinking water as a fundamental right. The Bill, along with prioritizing the needs of rural and urban households, also specifies other primary and secondary uses. Primary uses include water for agriculture, non-agriculture-based livelihoods and municipal water supply and secondary use includes water for commercial activities. The Bill also seeks to implement the principle of subsidiarity which involves giving communities the power to regulate groundwater at the aquifer level. For example, an aquifer situated entirely within the village will be under the direct control of the Gram Panchayat. In response to the Model Bill, so far, 11 states and 4 union territories (UTs) have adopted and implemented groundwater legislation. These are Andhra Pradesh, Assam, Bihar, Goa, Himachal Pradesh, Jammu & Kashmir, Karnataka, Kerala, West Bengal, Telangana, Maharashtra, Lakshadweep, Puducherry, Chandigarh, and Dadra & Nagar Haveli. Further, the Central Ground Water Authority issued an advisory to Chief Secretaries of all states and UTs to take necessary measures for adopting rainwater harvesting in all government buildings. So far, 30 states and UTs have made rainwater harvesting mandatory through laws, rules, and regulations and including provisions in building bye-laws.In addition, in the Draft Model Building Bye-laws, 2015, the Ministry of Urban Development has included a provision related to rainwater harvesting. It mandates rainwater harvesting structures in all buildings having a plot size of 100 sq. m or more. In order to promote efficient use of water and incentivize its conservation, the National Water Policy outlines the necessity for pricing water beyond basic needs. The policy proposes fair pricing for different uses through the establishment of a Water Regulatory Authority (WRA) in each state. WRA will fix and regulate the water tariff, to be determined on a volumetric basis and reviewed periodically. It may be noted that the implementation of the part of the policy that aims at providing basic access to water while establishing economic value and full cost recovery is a conflicting intention. In the absence of a suitable financial model, it remains to be seen how water will be allocated to users with limited capacity to pay for the cost. Additionally, it has been noted that the lack of clear guidelines and legally enforceable mechanisms makes the policy ambiguous and not ineffective.

Notes:- REPORT OF THE GROUND WATER RESOURCE ESTIMATION COMMITTEE

Post a Comment

image quote pre code